Management & Marketing

Farm Management/Operations

Laura has heard CSA farming referred to as “graduate level farming.” Their transition into producing crops for a CSA was gradual, because they bought certain crops from other farmers (described further under Finances) while renting land from Gardens of Eagan. It was not until 2009 that they grew all the crops they sold.

Figure 47: Adam and Laura use a variety of tools to manage their operations, from detailed spreadsheets to hand-written records. |

As alluded to earlier, the organizational skills needed for CSA farming can be one of its greatest challenges. After five years, Adam and Laura are just starting to feel like they have the planning aspects under control. They use a combination of spreadsheets, calendars, maps, and other tools to organize when and where crops will be planted and harvested and to track production and sales (Figure 47).

|

Laura and Adam consulted with other CSA farmers on organizational strategies but chose not to purchase customized software templates that are available for market farmers. They use Microsoft Excel to organize plans and schedules.

| Farmer’s Perspective: On the Bookshelf The Organic Farmer’s Business Handbook: A Complete Guide to Managing Finances, Crops, and Staff—and Making a Profit This book covers step-by-step procedures for making crop production more efficient; advice on managing employees, farm operations, and office systems; marketing strategies; and a discussion of the use of profits for business spending, investing, and retirement planning. A companion CD includes spreadsheets for projecting cash flow, a payroll calculator, comprehensive crop budgets for forty different crops, and tax planners. One of the reasons Laura and Adam like this new resource is because it covers production efficiencies (such as raised beds and standardized spacing) that they utilize. They also appreciate its advice on how to set up and keep straightforward crop enterprise budgets. It has inspired them to begin tracking the costs of production for individual crops. |

One of their keys to success is duplicating data just enough so that information is linked between different files and spreadsheets without doubling up on data entry effort or sacrificing the accuracy of numbers. Crops and varieties are grouped into categories, for example, as shown in Table 3. The crop categories and specific varieties then get placed into a seed inventory, where seed information (sources, organic vs. non-organic) and seed quantities (numbers used, in stock, and needed) are tracked. Seed varieties and starting quantities are then transferred to a greenhouse production data sheet, where propagation data (such as seeding dates and methods) get recorded. Key data from the greenhouse production records then get transferred to field planting data sheets (where planting dates; the number, location, and spacing of rows; and other information is recorded), and so on, until an entire production log is assembled for each crop.

Additional data sheets in the production log track the plants themselves (pest pressure, harvest dates, etc.), while others track the practices being used in the fields where each crop is grown (e.g., seeding and mowing of cover crops, application of fertilizer or soil amendments, irrigation, weed cultivation). Table 4 represents excerpts from the production log for beets in 2009. These records are essential for the organic certification process, though as described in one of their New Farm articles, Laura and Adam feel this “audit trail” would make them better farmers regardless of their commitment to certification.

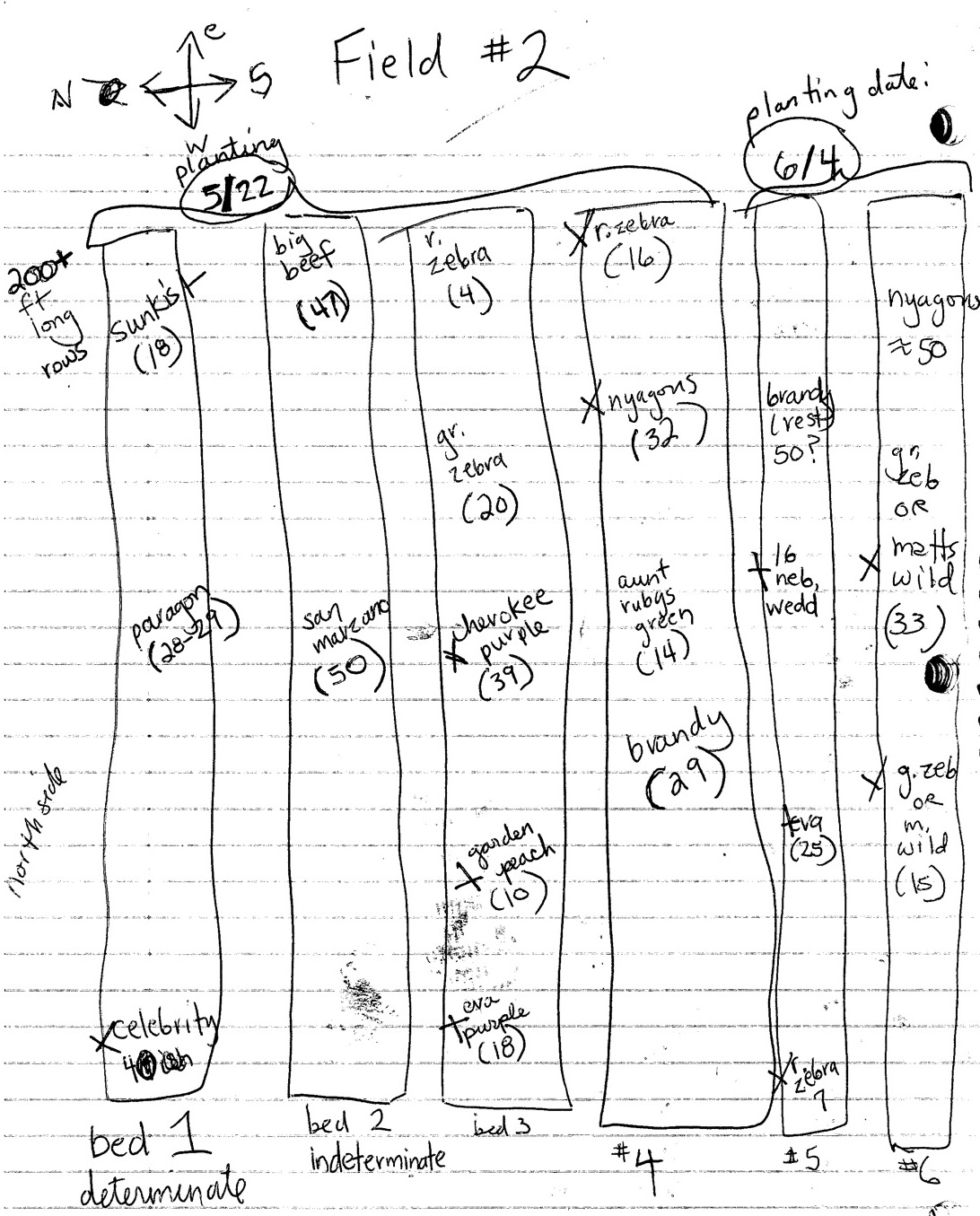

In addition to spreadsheets and printed data forms, Adam and Laura use a calendar to schedule planting dates and intervals for succession planting. They also use hand-drawn maps (Figure 48) to plan for and document actual plant spacing. In deciding when and how much to plant, they think in terms of each week’s CSA box and farmers market – what do they want to have in each box and at each market throughout the season? Then they count backwards to determine when to start the production process for each crop. In the beginning, they relied on seed supplier instructions plus trial and error, but now experience informs their decisions about how much crop to grow. Yields are highly variable, of course, depending on soil fertility, weather, and so many other factors; in order to mitigate these variations, Adam and Laura overplant some crops by 20% if space allows. |

Educator’s Perspective: Resource Tip Organic Documentation The effort required for recordkeeping in organic certification can be daunting at first, so it helps to start out with templates. Organic Field Crop Documentation Forms is a set of forms from ATTRA that can be photocopied. Appendix A of Organic Certification of Vegetable Crops from the University of Minnesota Southwest Research and Outreach Center has step-wise instructions, recordkeeping tips, and example formats for data sheets. |

Laura and Adam have learned that there are pros and cons to every recordkeeping system and that systems evolve. There is some give-and-take, for example, when it comes to deciding whether a pre-made data sheet or a blank notebook will be the best way for documenting the information needed at different stages of production and planning. They acknowledge that, as far as they’ve come, their system is still a work in progress.

Figure 48: Laura and Adam use hand-drawn maps such as this one, for their 2009 tomato crop, to track field production in combination with spreadsheets and calendars.